As a continuation of the Fee-Only Financial Advisor blog sharing group, this month’s post comes to us from Ann Garcia, a Financial Advisor in Portland, OR. She shares her thoughts on saving for college and some of the myths surrounding the idea that one can be penalized for college savings by receiving less financial aid.

One of the most persistent—and pernicious—myths about college planning is that parents who save are penalized in the financial aid process for doing so. Perhaps you’ve heard, or even said, this: “I’m better off not saving for my kids’ college because I’ll just end up getting less financial aid if I do.”

It’s a common misperception and like many such misperceptions, it starts from a kernel of truth: Both the FAFSA and the CSS PROFILE ask you to report your assets as of the date you file their respective forms. And under the “assets” heading you’ll need to report on the FAFSA almost everything other than your retirement savings and primary residence, and on the CSS PROFILE essentially your entire net worth. But while the information requests are transparent, it takes some digging to understand what the formulas do with that information once you’ve reported it.

How Aid Eligibility is Calculated

The FAFSA is almost entirely income-driven. The formula allocates modest allowances against income—roughly the federal poverty rate for a family your size plus adjustments for taxes and a few other nominal items—and then assesses the remainder on a progressive scale which quickly reaches 47%. Which is to say that above a very modest income level, an additional $1,000 of income increases your Expected Family Contribution (EFC) by $470.

Assets get a different treatment. Net of allowances—generally around $19,000 for married parents or $7,000 for single parents—assets are only assessed at 5.64%. That means an incremental $1,000 of assets only increases your EFC $56, and only if you already had another $18,000 in non-retirement assets.

The CSS PROFILE, on the other hand, looks more at total net worth, but again income is the largest component of the formula. (Unlike the FAFSA, the CSS PROFILE offers schools leeway on what data they collect and how they calculate different items, so there isn’t a specific formula to point to.) In general the CSS PROFILE gives a slightly larger asset protection allowance than the FAFSA, but it also counts additional assets such as home equity. And similarly, it assesses assets at a fairly low rate.

The FAFSA 4caster, while not necessarily the most accurate predictor of your EFC, will at least give you a very helpful sense of how much savings would “hurt” you in the aid formula. Just plug in your data, then increase your assets by $10,000. The CSS PROFILE does not have a comparable tool; however, if PROFILE schools are among those you are considering, you can do the same exercise with their Net Price Calculators (generally found on the school’s admissions and/or financial aid web pages).

Need-Based Financial Aid

The college savings penalty myth has a corollary myth: that having a low EFC ensures that you will get gift aid. In fact, there is no requirement that schools meet your need; the phrase “need-gapped” refers to the situation where the offered aid does not make up the difference between the student’s EFC and the cost of attendance. And even when an aid package meets 100% of need, it’s highly likely that loans and work study are part of that package. According to the College Board, over 1/3 of undergraduate financial aid came in the form of loans.

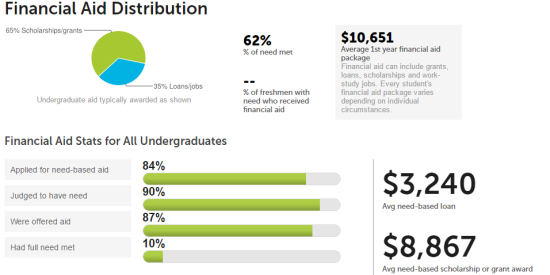

Here’s an example of the breakdown of total undergraduate aid dollars from an actual public university:

While most of those who applied for need-based aid received it (90%), only 10% had their full need met and less than 2/3 of the total need was met. Plus, comparing the average need-based loan to the average need-based scholarship shows how a large portion of that need is being met. Of course, every school has its own policies; you can get research schools you are considering at the College Board’s website.

In this case, a family that chose to forego savings in order to get more financial aid would find that their efforts were not very productive: They may or may not have received any aid at all, and even if they did it would not likely have met their full need, and even if they did they would still have loans.

Expected Family Contribution

A further consideration in choosing whether or not to save is this: Can you even afford your EFC? A family of four with income of $150,000 and minimal savings will have an EFC somewhere around $17,000. That means that the family is expected to spend the first $17,000 of college costs before aid kicks in. In contrast, if that same family had saved enough to have $5,000 annually for each student (let’s make it simple by saying they have $40,000 in assets when filling out their first FAFSA), their EFC would go up by about $1,400 the first year, but they would still come out ahead by $3,600 because of their savings. And as they spend down those assets, their EFC would go down as well.

Most families cannot come up with their EFC without some form of savings or borrowing. In effect, the formula is telling you that you need to save, because a family of four with $150,000 of income is unlikely to be able to hand over $17,000 out of pocket each year—but that family did have 18 years to come up with some savings. And if their aid package already includes loans, that leaves less borrowing options available.

The Subjective Side

Here is what an Occidental College financial aid officer had to say about families with high incomes and no savings: “I see so many well-to-do families appeal because of a job loss, and then you ask about assets and they have none. How can you have no assets when you’ve been making six figures for more than a decade?” Colleges expect that families have 18 years to prepare for college, and so they expect families to have some savings. Aid awards can have a subjective component to them—although EFC is determined and federal dollars must be allocated by formula, the college has some leeway in allocating institutional dollars in lieu of loans—so families should be aware of how a lack of savings might be perceived.

While it’s true that savings count in the aid formulas and can increase a family’s EFC, not saving for college will generally leave a family in far worse shape than does saving.

About the Author:

Ann Garcia, CFP®, is a fee-only fiduciary advisor and owner of Independent Progressive Advisors in Portland, OR. She also blogs about college planning as The College Financial Lady.